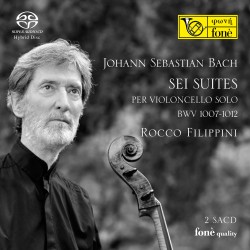

STUDIES ON LINEAR COUNTERPOINT: SIx SUITES FOR CELLO SOLO (BWV 1007-1012)

By Johann Sebastian Bach

Rocco Filippini kam 1943 in Lugano (Schweiz) als Sohn eines Literaten und Malers und einer Pianistin zur Welt. Er kam schon früh mit Musik in Berührung und begann entsprechend früh mit seiner musikalischen Ausbildung. Mit 17 Jahren erhielt er das Diplom am Konservatorium in Genf. Seitdem spielte er auf vielen namhaften Bühnen und Festivals der Welt (Salzburger Festspiele, Rossini Opera Festival) und eignete sich ein sehr breites Repertoire an, das vom Barock bis hin zu zeitgenössischer Musik reicht. Er war Dozent an verschiedenen Hochschulen wie dem Giuseppe Verdi Konservatorium in Mailand oder der Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rom. 1985 gründete er mit drei Kollegen die Walter Stauffler Akademie in Cremona, die sich der Ausbildung von Musikern mit Saiteninstrumenten widmet.

Für die vorliegenden Aufnahmen bei Fon spielte Filippini sechs Suiten von Bach ein, wobei er eine schier unglaubliche Präzision und Ruhe an den Tag legt. Gleichermaßen souverän entlockt er seinem Instrument leise, sanfte sowie kräftige und rauhere Töne. Auf faszinierende Art und Weise zeigt Filippini, wie vielse/aitig das Cello ist und führt den Zuhörer einfühlsam durch die sich immer weiterentwickelnden und sich steigernden Motive. Diese Meditation für die Ohren sollte man sich nicht entgehen lassen!

Conceived, recorded and produced by: Giulio Cesare Ricci Recorded at: Volterra, Italy, Persio Flacco Theatre, August 2012 Musical assistant: Cosimo Filippini

Recording assistant: Paola Liberato

Digital DSD editing: Antonio Verderi

Valve microphones: Neumann U47, U48, M49

Mike pre-amplifiers, cables ( line, digital, microphone, supply ): Signoricci

Recorded in stereo DSD on the Pyramix Recorder using dCS A/D and D/A converters Photos by: Cosimo Filippini and Studio Russo / Lookland

In co-production with Festival Internazionale del Val di Noto “Magie Barocche

and the Artistic Director Antonino Marcellino

The Six Suites for cello solo here recorded were performed at 4 Festival Internazionale del Val di Noto “Magie Barocche (Militello in Val di Catania, Italy, Church of Santa Maria della Stella, 31st

The most remarkable, unexpected, and surprising of the works that came to light in Kthen, where Bach worked from December 1717 to April 1723, are those for violin and cello that Johann Sebastian conceived without the support of any accompani- ment, entrusted to either a figured bass or to a cymbal playing in alternating con- certante manner.

The two collections each comprising six compositions arranged to an overall scheme presumably with the view to a printed edition differ both in content and form, but are in some ways complementary. The first collection to be compiled was probably the one with the works for unaccompanied violin, as would be attested by the original manuscript, whose frontispiece reads: Sei Solo. | a | Violino | senza | Baßo | accompagnato. | Libro Primo. | da | Joh: Seb: Bach. | ao. 1720. The work (which has come down to us in six other copies made by different hands, one by Anna Magdalena Bach) includes three sonatas and three suites (BWV 1001-1006). The al- ternating succession of sonatas and suites (the latter made up of a series of dances, in one case preceded by a prelude) should not however be seen as a succession of six entirely autonomous and independent musical entities (even if Bach speaks of Sei Solo, typical of the editorial custom of the age), but rather as the presentation of three couples of compositions of which the second term or member of the couple is the continuation or corollary of the first; in other words, what we have is integral sonatas, a suite of dances as it were, following a tradition that was by no means rare for the music of the time.

It is possible that the collection containing the Six Suites for Cello Solo was conceived as Libro Secondo, as the second element of a multiarticulated but substantially co- herent compositional project with the aim of playing off the technique da braccio string instrument with that da gamba string instrument. Unfortunately, the work has not reached us in the original manuscript, which perhaps would have enabled a better understanding of the issue, but rather in copied form; four are known, two of which made a short while after the creation of the collection. However, the most important of these copied manuscripts is the one made around 1730 by Anna Magdalena Bach-Wlcken (1701-1760), the composers second wife, and entitled: 6 | Suites a | Violoncello Solo | senza | Basso | composes | par | Sr. J. S. Bach. | Maitre de Chapelle. The copy was made by Anna Magdalena, together with that of the Sonate e Partite per violino solo, at the behest of a violinist who was active in Wolfenbttel, as the Kammermusikus at the Court of Braunschweig-Wolfenbttel, namely Georg Heinrich Ludwig Schwanenberger (Schwanberg). He was a native of Helmstedt (where he was baptised on 10 March 1696), a former pupil of Bach at Leipzig in 1727/28, and died in Wolfenbttel on 15 December 1774. The two manuscripts were then passed on to Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749-1818), the first biographer of Bach, and later to Georg Poelchau (1773-1836), one of the most im- portant collectors of Bachian manuscripts, to be finally purchased, in 1841, by the Knigliche Bibliothek of Berlin, the same that today after the events leading to the reunification of Germany bears the name of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz and that conserves them under the original shelf mark P 268 (works for violin) and P 269 (the Cello Suites).

The copy of the Cello Suites undertaken by Anna Magdalena, believed for a long time to be an original (the spouse excelled in imitating Johann Sebastians hand- writing), was nevertheless preceded (around 1726) by one made by a student of Bachs, Johann Peter Kellner (1705-1772). Then there were a further two anony- mous copies, one from the mid-18th century and the other at the end of the cen- tury. It was not until 1824 that the collection was issued when the Paris publishers Janet et Cotelle presented an edition to the public entitled Six Sonates ou Etudes Pour le Violoncello Solo Composes par J. Sebastian Bach. uvre Posthume and advising the reader: [...] cet uvre na jamais t grav, il tait mme difficile de la decouvrir. Aprs beaucoup de recherches en Allemagne, M. Norblin [Louis Pierre Norblin, 1781-1854], de la musique du Roi, premier violoncelle de lAcadmie royale de Musique, a enfin recueilli le fruit de sa persvrance, en faisant le dcouverte de ce prcieux manuscrit. The term suite, by now archaic and little appreciated by the public, had been replaced by sonata, more becoming to modern tastes, and tude, this latter used to better define the didactic purpose of the edi- tion and hence its greater saleability.

With the compositions devoted to the violin and cello without the accompaniment of any other instrument, Bach intended to develop a concept of primary impor- tance: the linear moment of counterpoint, of a polyphony conceived not as a vertical organisation of the phrase following the principles of pure canonic imita- tion and tonal harmony but rather as a rigorous and symmetrical objectification of the melodic and rhythmic properties of musical language, by virtue of its repre- sentation in space and time.

The logic of the passage, so that it is punctuated in particles reappearing at regular moments on the different strings of the instrument, thereby giving shape to rep- resentations in the form of imitation, and the force that the movement impresses on the discourse, almost so that each element is endowed with its own kinetic en- ergy, create a musical picture, a construction in which the line counts more than the whole and in which the art of the cantabile is the genuine raison dtre of the composition. If in the violin compositions the problem of the unaccompanied style is tackled with a two-fold formal aspect (sonatas and partitas, the latter as aforementioned as continuations and integrations of the former), but connecting the whole to a homogeneous and coherent architectonic principle, in those for the cello instead there is only one form: introduced by a prlude set before each suite in different style each of the six compositions envisages the regular succession of the customary dances for the genre (allemande, courante, sarabande, gigue), inserting between the third and fourth dance a menuet I and II in the suites I and II, a bourre I and II in the suites III and IV and a gavotte I and II in the suites V and VI.

An obligatory reference point for the Bach collections must have been the rep- ertoire of the viola (viola da gamba), which had achieved noteworthy results in France and Germany. In effect, it seems reasonable to think that Bach wished to modify an intention, a project formulated with an eye to the viola and then focus- ing on the violoncello, almost to try applying to the latter instrument, which still lacked truly interesting works, a technique that tradition had entrusted to the viola.

The hypothesis might also be confirmed in the particular nature of the last two suites, to whose instrumentary changes were made or with the provision of a dif- ferent tuning or again with the use of an anomalous sonorous instrument. In this view, and bearing in mind that the collection is largely conceived with an eye to- ward French got (all the titles of the single movements are in French), it seems logical to trace Bachs suites back to the models that had been provided abundantly over the last decades by Marin Marais and Johannes Schenk for the viola, to the majestic basse de viole.

The tendresse, the dlicatesse of those pages exemplary manifestations of the Courts taste may be found in Bachs compositions, both at infinitely more re- fined levels; the proliferation of the melodic material, which was one of the es- sential stylistic features of the way the French masters built up the discourse, was taken up as a firm rule by Bach, but reversed on the level of novel polyphonic struc- tures and on an instrument that had not yet found its way in competing in subtlety and splendour with the viola. In a word, Bach invented the style of the violoncello and signed the beginning of the irrevocable decline of the ancient 6-7 string instru- ment to which, among other things, the Kantor did not spare himself by dedicating it pages that, needless to say, are the finest of that golden repertoire.

Perhaps the idea did not meet with the approval of contemporaries and the collec- tion was late in coming out of the Bachian circle to then be issued widely in print, as we have seen, in the form of a collection of sonatas or studies (the one issued in Vienna published by Heinrich Albert Probst followed a year after the 1824 edition, with exactly the same title and hence misleading regarding its original appear- ance). The claimed didactic nature of the work evidently stemmed above all from the difficult impact with the introductory passages: those six prludes not only represent a sampling of cultured technical difficulty with the continual recourse to a linear notion, expanded in persistent and repetitive figures, sustained by pedal tones to the extremes of obsession, by harmonic mutations in progression, by re- curring rhythmic figures, by the regular pulsating alternating of free or informal notes and legate, by insistent shifts in scale, but also obey a musical conception in which the exercise, the exercitium is the only basis on which to master and acquire the meaning of the music. In other words, the language manifested in these com- positions is primarily made up of rushed phrases, projected ahead, the exception of the complex prlude of Suite V), albeit technically challenging.

A rhythmic-melodic formula declared immediately on opening, without preamble, indicates along which lines the entire movement should proceed. The continuity of the discourse then brakes, it rears up in stops that almost enable recuperat- ing the energy spent to bring the page to successful completion; the stop is also a pretext for the changing of the figure and at times (Suite V) also the metre and style and proves ever more opportune when the page is exceptionally broad and ex- tended (Suites V and VI). The pace, the dynamic contrast, even the timbre stem- ming from the different colours of the strings and changes of register, the plays on piano and forte (especially in Suite VI), the figures in virtuosic cadence and free toccata are the typical notes, the hallmarks of the prludes, highly serious pages, of great symmetric precision and governed by an ingale rhythmic conception, typi- cally French.

The symmetry in particular also steers the various dances, one of which the sarabande that Bach sets at the heart of the suite proper again has an intensely expressive nature. The composition is still contained in a few bars, whose number varieseachtime,butonthebasisofmultiplesof4(I=8+8;II=12+16;III=8+ 16;IV=12+20;V=8+12;VI=8+24)andtherhythmicfigureswithinarevari- ously arranged, leading to an incomparable range of architectonic combinations. The jovial Italian style, expressing joy and freedom, seems to dominate most of the other dances, excepting a courante (that of Suite V, an entirely French page, beginning with the prlude itself, conceived as an ouverture) and three allemandes (suites II, III and VI).

The last two suites present a number of more specific problems. We have already mentioned the greater breadth of their prludes and the particular form of the one opening Suite V, conceived in the style of an ouverture, with an ample fugue (whose subject has openings arranged on various strings in the order the 2nd, the 1st, the 4th and the 3rd to achieve, through their different colours, the poly- phonic effect). This Suite V, in C minor, also has the particular quality of being written for an out of key cello, that is with an anomalous tuning: DO1 SOL1 RE2 SOL2, instead of the customary DO1 SOL1 RE2 LA2; thus, the 4th string is tuned one tone under the norm.

Suite VI is written for a five-string instrument the copy made by Anna Magdalena simply has the indication Suitte 6me cinq acordes without specifying the kind of instrument, which nonetheless should be a five-string instrument). By habitual custom, it is held that the instrument to which this suite refers is the viola pom- posa. An instrument, according to the affirmation by Frantiek Benda (who made visits to Thomaskantor in Leipzig in 1734 and 1738), that was invented by Bach himself and would have been tuned like a violoncello, but with an additional high- note string, larger than a viola and equipped with a band that enabled tying it to the chest and arm. Nonetheless, it is by now widespread opinion that the 18th century sources relating the information had confused the five-string violoncello (the so- called violoncello piccolo) and the viola pomposa, whose invention should not be attributed to Bach, but rather to a lute maker from Leipzig, Johann Christian Hoffmann (1683-1750), who made the new viola at the Thomaskantors request. Three examples of viola pomposa made by Hoffmann are still conserved today (out of ten known in the history of the lute maker) and dated 1732, 1737 and 1741, hence many years after Bach created the collection of the suites for cello.

While compositions by Bach for the viola pomposa (the instrument has a mod- est literature of only four compositions) are unknown, it is acknowledged that he used the violoncello piccolo on a number of occasions (as testified by nine canta- tas: BWV 6, 41, 49, 68, 85, 115, 175, 189 and 183, all from 1721-1726) and it is to this latter (five-string) instrument that Suite VI for solo cello should be connected even if as recognised the composition may also be performed on the normal four-string cello, provided that one is particularly committed at a technical-virtu- oso level, given the breadth of range (more than three octaves) that are decidedly greater than the norm.

Court music, chamber music of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Kthen who was a pas- sionate enthusiast of music, is the hypothetical intention for the collection of the Sei Suites a Violoncello solo, like that of the Sei Solo a Violino senza Basso accom- pagnato that preceded it. If this were so, the work could have been entrusted to the expert hands of a virtuoso such as the violoncellist Christian Bernhard Linigke (1673-1751), the member of an important family of musicians of Brandenburg, formerly active in the Court Chapel of Berlin (1706-1713), then until March 1716 in that of the Margrave of Brandenburg Christian Ludwig (the dedicatee of the Six Concerts avec plusieurs Instruments, or the Brandenburg Concertos), to be taken on finally (May 1716), as Kammermusikus, in that of Kthen, where he would have carried out his duties until his death. However, there we cannot be certain and the field is still open to many solutions. Perhaps it was the theoretical and experimen- tal aspect, more so than the practical, that was much closer to the Kapellmeister. The instrumental music he produced up to then was dedicated to keyboard instru- ments: at Kthen he inaugurated a new line of research, not subject to the current execution practices, to deliver to the people a constitutional dictate of immense grandeur and power, a line of study, however, that was not to find a following until times nearer to us. Nevertheless, of that reservoir of invention, there were those who had the foresight to understand its importance towards the end of the 19th century. It is not surprising to read what Alfredo Casella wrote in the I segreti della giara (1941), with regard to his father Carlo (1834-1896), violoncellist, who he indicated as the masterful performer of the Bach suites.

Alberto Basso

Titel:

Sacd 1:

Suite I BWV 1007 in sol maggiore/in G major

1 Prlude 2.32

2 Allemande 3.38

3 Courante 2.24

4 Sarabande 2.50

5 Menuet 3.02

6 Gigue 1.47

Suite II BWV 1008 in re minore/in d minor

7 Prlude 3.25

8 Allemande 3.06

9 Courante 1.57

10 Sarabande 4.07

11 Menuet 2.58

12 Gigue 2.33

Suite III BWV 1009 in do maggiore/IN C major

13 Prlude 3.27

14 Allemande 3.20

15 Courante 3.02

16 Sarabande 4.11

17 Bourre 3.17

18 Gigue 3.03

Total tracks time: 54.48

Sacd 2:

Suite IV BWV 1010 in mi bemolle maggiore/in E flat major

1 Prlude 3.55

2 Allemande 4.01

3 Courante 3.29

4 Sarabande 4.08

5 Bourre 4.28

6 Gigue 2.32

Suite V BWV 1011 in do minore/in c minor

7 Prlude 6.27

8 Allemande 5.47

9 Courante 2.06

10 Sarabande 3.01

11 Gavotte 4.28

12 Gigue 2.17

Suite VI BWV 1012 in re maggiore/IN D major

13 Prlude 4.47

14 Allemande 6.51

15 Courante 3.32

16 Sarabande 4.50

17 Gavotte 4.10

18 Gigue 4.00

Total tracks time: 74.56

Datenschutzbedingungen (bearbeiten im Modul "Kundenvorteile")

Datenschutzbedingungen (bearbeiten im Modul "Kundenvorteile")

Lieferbedingungen (bearbeiten im Modul "Kundenvorteile")

Lieferbedingungen (bearbeiten im Modul "Kundenvorteile")

Rücksendebedingungen (bearbeiten im Modul "Kundenvorteile")

Rücksendebedingungen (bearbeiten im Modul "Kundenvorteile")